The Unicomp Ultra Classic

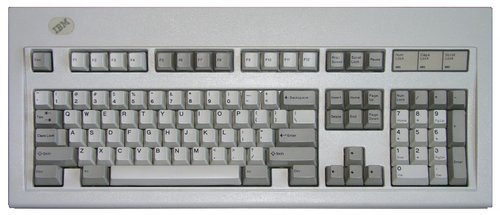

Mechanical keyboards. Love them or hate them, there is a huge community around them now and they are quickly becoming the hot commodity of choice for gamers—at least if Razer has anything to say about it. However, underneath the mainstream layer of gaming-oriented keyboards there is a deeper level. This dark corner of the internet harbors a scoffing contempt for the flashy RGB lighting and ugly illegible keycaps of keyboards you’d find at Best Buy. No, this “cult” of keyboard enthusiasts has a venerable leader: the IBM Model M.

Back in ye olden days, when the term “IBM Compatible PC” actually meant something, computers typically came with mechanical keyboards. Since the PCs were so expensive, companies like IBM often went all-out in their keyboard designs, distributing hefty boards of their own make or commissioned from third-parties like ALPS Electric, who would often manufacture custom-branded keyboards for OEMs. Many of these keyboards would go on to become legendary in the mechanical keyboard community; the idea of “they just don’t make ‘em like they used to” is prevalent here, and honestly there’s some truth to it.

The Model M was a particularly tanky piece of hardware distributed by IBM with their computers in the 80’s and 90’s. It gained renown for being massively heavy, resilient, and fun to type on. In particular, the key mechanism is perhaps the most well-regarded of all keyboards, barring particularly rare examples like IBM’s own Model F or the exceptionally uncommon ALPS SKCM Blue. Using a fairly simple design involving a spring depressed by the keycap until it buckles, IBM was able to achieve an extraordinary typing experience with a relatively simple and therefore durable mechanism. I’ll talk more about the feeling of using a Model M in a bit.

IBM's "Space Saving Keyboard" Model M Variant (Wikipedia)

As the 90’s continued, PC prices began to drop. Increasingly, manufacturers began including cheaper keyboards with their computers to keep costs low. After a short era of “somewhat cheaper” mechanical keyboards, finally the dreaded rubber dome keyboard became the go-to option for companies like HP, Dell, and so on. IBM held on admirably long, manufacturing the Model M through third parties like Lexmark for many years. Of course, even IBM had to cut costs; the younger Model M boards are notoriously lower quality than the older ones, though they were never slouches.

By the mid 90’s, however, the writing was on the wall for the Model M. While other companies continued to make them for a few years after, Lexmark stopped making Model Ms in 1996. This is where Unicomp comes in. In what is now a relatively well-known story (at least in the mechanical keyboard community), some Lexmark employees purchased the tooling used to make the Model M boards and formed a new company: Unicomp.

Unicomp continues the Model M legacy to this very day. They’re still out there in Kentucky cranking out new designs based on the Model M, using the same tooling that Lexmark used in the 90’s. While purists will certainly want to hit up eBay for a real Model M, complete with IBM badge and the clout that goes along with it, the Unicomp keyboards are pretty much the exact same thing. I have been typing this entire article on a Unicomp Ultra Classic, one of their slightly-redesigned takes on the now-legendary behemoth.

Enough with the history lesson. Let’s talk about the Ultra Classic. As I hinted at earlier when I said that I’d talk about the feeling of using a Model M later, the Ultra Classic is almost exactly the same. The keys are incredibly responsive. Every key has a very obvious tactile bump, occurring when the spring buckles. The bump synchronizes perfectly with the click sound, since they’re both generated by the same spring action. Tactility is part of the reason these keyboards are so popular among serious typists. Feeling and hearing exactly when the switch actuates allows you to type more accurately, and it just feels great to get feedback from each key press. Additionally, the keys have a lovely springiness on the return as you let off the key as well. This is surprisingly essential to a good typing feel. Without it, your fingers end up doing more work to move to the next key. Speaking of finger work…

Unicomp Buckling Spring (Wikipedia)

The keys on these boards require a surprising amount of force to actuate. If you’re not used to stiff keyboards (like many old ALPS boards or modern Cherry MX Green boards), you will make a lot of mistakes at first. As you attempt to strike a key with your ring finger or pinky and fail to press the key hard enough, you’ll learn why people often compare these things to typewriters. The amount of finger-strength required to operate a Model M is a love-it or hate-it kind of deal. While anyone can get used to it, some people just can’t get past it. Personally, I find that the keys are easier to actually type on than some supposedly lighter switches like Cherry MX Blue. Sure, Cherry MX Blues are much lighter to press, but the switch has a large amount of hysteresis, where the switch’s return point isn’t the same as its actuation point. Because of this, I find myself hammering the ever-loving crap out of Blues, and lifting my fingers entirely from the keys so that they reset before pressing them again. It feels more laborious when compared to the Model M, where you can type smoothly once you beef up your fingers.

Pressing keys slowly, you’d almost think you were typing on a typewriter. The sound is very satisfying; it is a loud click with a small metallic twang at the end. Once you really get going and start actually typing on this thing, well… to me it sounds like the 80’s. A cacophony of clicks and clacks and pings that I personally find very fulfilling, but people around you will find miserable. The bad thing about the weight and quality of these boards is that when you use one at work, your coworkers are going to bash your head in with it. I can’t stress enough how incredibly loud this thing is. Every key press sounds deliberate and important, like every stroke is a decision. When you think of movies where stereotypical nerds are hacking the Pentagon or whatever, you imagine this sound as they slap the keyboard with incredible speed to send their viruses through the firewall or some other gobbledygook. Much like the stiffness, the sound is also love-it or hate-it.

So the typing experience is amazing, if you can get into stiff but responsive tactile keys and an iconic sound that might leave you with tinnitus. There’s something about the smoothness of these boards; they’re legendary for a reason, although modern sensibilities might make one hard to get accustomed to. When the Model M was in its prime, loud keyboards and stiff keys were the norm, but they were built that way for a reason. It’s just satisfying, in a sort of primal way. You really do feel like you’re working on something important when you type on a Model M or one of its descendants.

Now for the bad news. One of the other reasons that IBM Model M boards were so revered was their legendary durability. Unicomp’s Ultra Classic lacks a lot of that toughness. While the keycaps are incredibly high quality, the chassis of the board itself is quite lacking. My Ultra Classic has an obvious seam on the front of the board, where the top plastic shell meets the bottom. It’s right below the space bar, and it feels incredibly cheap. It even seems like it’s separating at times, prompting me to press down on the bezel to try and secure it. The board is creaky; whatever plastic they built this thing from is not strong enough to hold the beefy materials within, because just pressing on it causes it to creak like a crappy toy. It doesn’t feel like it’s going to break under normal use or anything, but even the younger IBM boards were built better than this.

Some drawbacks of the board are shared with the Model M. For example, the keyboard does not have N-key rollover, meaning in many cases you’ll only be able to press two keys at the same time. In my testing I found that any two of WASD, plus E, Q, or R could all be pressed at the same time, so it’s possible Unicomp put some thought went into making the keyboard usable for gaming. However, given the huge amount of force required to press the keys, it’s not fun to game on a Model M or the Ultra Classic. You’re not going to enjoy trying to repeatedly tap any of these keys.

For the most part, the keys on the Ultra Classic are pristine. However, the End key on my board sounds like the spring is misaligned; you can hear the spring scraping when you press it. The Page Down key sounds like the plastic of the keycap is rubbing against something, and it seems to actuate lower than the other keys. In fact, key consistency is a big problem on this board. The Escape key sounds amazing, with a deep thock sound, while the Caps Lock key barely sounds like a buckling spring at all. For what it’s worth, the keys you’re going to be using 95% of the time—the alphanumeric keys—all feel pretty consistent. However, when compared to an IBM-made beast, the Unicomp comes up short in a few ways. To be fair, Unicomp boards are vastly cheaper than even the youngest IBM-made Model Ms were, especially accounting for inflation. In some ways I guess you get what you pay for.

That’s the Unicomp Ultra Classic. An amazing piece of history, slightly misremembered through the fog of time, made so that a new generation of folks can appreciate the typing feel of an old legend. If you like the idea of the Model M but don’t want to deal with the potential quality issues of the Unicomp boards, you can always take your chances on eBay. Authentic IBM Model Ms are always available, but quality and cleanliness will vary significantly. New-in-box Model Ms are quite expensive and still not guaranteed to work since they’ve likely been sitting around for 25-35 years. I totally recommend picking up a Unicomp instead. They’re new, they’re USB, and while there are a few quality problems, they’re honestly pretty affordable boards when you pit them against the latest RGB lightshow from Razer. With a vastly superior typing experience, but admittedly inferior gaming experience, these are truly satisfying keyboards for typists and programmers alike.