Times Square by Francisco Diez, CC BY 2.0

Like most software engineers in the futuristic year of 2025, I sometimes use LLMs like ChatGPT to help me write code. Especially for tedious, but well-solved problems like writing common regular expressions, I give my brain a break as a little treat. The LLM acts as a glorified search engine and strings together something which is good enough for what I need in the moment. It’s a win/win: I didn’t need to exert any real brain power, and the problem got solved. Really, that’s what software engineers are. We’re problem solvers. And the problem got solved.

Right?

… Right?

Yeah, you know where this is going.

(Edit 2025/07/30: I don’t usually edit my articles after the fact, but the previous version of this one contained a particularly vitriolic admonition of the start-up/venture capital game which probably wasn’t entirely fair. This new version tones down the bile a bit.)

What is Vibe Coding?

If you aren’t aware already, let me introduce you to an idea which has gained popularity lately: vibe coding. To summarize, it’s a term for when someone isn’t actually writing any code; they’re simply prompting an LLM to generate code for them based on a description of their intent. Then, they copy/paste that code into their editor and tweak stuff until it builds and produces the results they’re looking for. Repeat ad nauseum until the task is complete.

The vibe coder has completed their work without ever needing to engage the engineering part of their brain. They probably “produced” more lines of code in less time than another developer who wrote it all themselves. However, perhaps controversially, I’m going to argue that if you’re a professional developer, you need to stop solving problems and instead become a problem solver. Let’s talk about the difference.

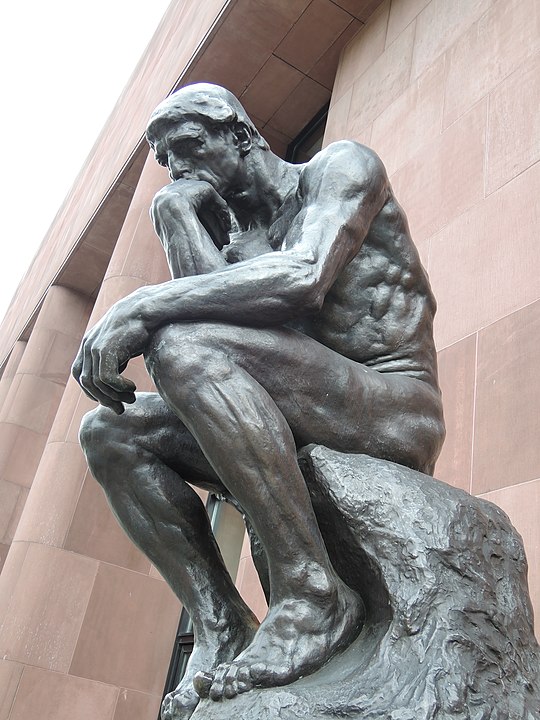

This guy is definitely a professional

First, we’re going into this conversation with a few assumptions. Most importantly, note that I specifically call out professional developers. A hobbyist or general user who needs a script or a custom application gets no judgement from me, no matter how they achieve their goals. This (one-way) conversation is between me and engineers working for companies, producing software on a daily basis. Presumably, that software is used by a customer or stakeholder of some sort to create value, and they are paid for their labor, making them a professional.

Another foundational principle here is the idea that software engineering is a discipline worthy of refinement. I don’t want to engage in this conversation with tech bros who lack respect for the trade which pays their bills. Those people are often incapable of having a good faith discussion on this topic because their fundamental philosophies do not align with long-term goals. Their objectives are usually very short-term, lack an overarching strategy, and originate from a mindset geared toward playing a very different game. It goes without saying that vibe coding is very popular with the sorts of people who see programming as a necessary evil on the path to getting bought by Amazon.

The Difference Between Solving Problems and Being a Problem Solver

You know who gets left in the dust when hype bubbles burst? You and I. Thankfully, we can pick ourselves back up, get back on the job market, and go apply our skills elsewhere as engineers—as problem solvers. Unless you’re not a problem solver.

Using an LLM to vibe code certainly takes more skill than browsing the internet. You’ve got to have some intuition on how programming might work, and enough sense to generally grok the syntax of whatever language you’re using. You need enough to make minor changes, at least. But don’t fool yourself. Software engineering, architecture, infrastructure, data science, etc. are all extraordinarily complex and nuanced fields. They’re packed full of decades of hard-learned lessons forged in the real pressure of projects where millions of dollars are at stake. Your own experience comes from passively absorbing the mentorship of your senior colleagues, making your own mistakes, active learning, contributing to projects, and slowly diamondizing.

Use your noodle

The most important experience, though, is problem solving. It’s a mindset like a muscle, and you have to train it. Anyone can vibe code because everyone can more-or-less wrap their head around what a programmer does on the surface: write instructions to make a computer do something. The ability to proficiently solve complex problems—to break down confusing, nuanced, sparsely detailed, or misleading issues and turn them into achievable and actionable objectives—isn’t something an LLM can do for you. Your value as an engineer isn’t your ability to write code, it’s your ability to be a problem solver. You can only exercise the muscle if you use it.

Interestingly, you’ll find that being a problem solver is important in more than just programming. It’s a skill applicable to your entire life and across every career. Employers need problem solvers because someone has to figure out what to do when unexpected things happen. Science needs problem solvers to discover the undiscovered. The world needs problem solvers to navigate the unprecedented.

Vibe coding robs you of valuable problem solving experience, because you’re not solving any problems. The LLM is. In order to survive in this industry, you can’t be disposable. You need to be indispensable. You need to be a problem solver.

Prompts != Problems

I’ve had a couple of discussions very similar to this with colleagues and… let’s call them “industry pundits.” Frequently, there are two counterpoints to my perspective on vibe coding.

- Good faith argument: successfully writing prompts to coerce the LLM into giving you the results you need is similar to writing code, and therefore contributes to one’s problem solving experience.

- Bad faith argument: the tech industry is in a post-principle state; no one cares about any of this stuff anymore. The only thing that matters is slinging code well enough to get to the next round of funding, or to keep operations running, or whatever.

Firehose by Jip Valentijn, CC BY-SA 2.0

Let me be very grim and serious for a moment. We’re going to talk about #1 later, but anyone who tries to legitimately pitch #2 to me? They can fellate a firehose. Like so many of the problems plaguing the world at time of writing, the toxic idea that we’re in a post-discipline world is a dangerous lie. It comes from a) people actively invested in devaluing your skills to drive down their labor costs; b) grifters looking to maximize their short-term gains at the expense of overall customer satisfaction or long-term sustainability of the business; or c) hawkers looking to increase the perceived value of AI. The degradation of principles in the tech industry is directly correlated to the enshittification of the products and services it offers, which is itself inseparable from a market ruled by the FAANG-like goliaths terrified they can’t keep the financial line going up forever. I won’t be gaslit by these people, and neither should you.

We good? Okay. Let’s talk about prompts vs. problems.

Perhaps the biggest difference between solving a problem yourself and crafting a prompt is in how you engage your brain. Engineering is a declarative action. Compare it to building a bookshelf. You understand what the bookshelf should look like, what kinds of tools and supplies you need to build it, and—if you know what you’re doing—viable dimensions and construction methods that are likely to result in a stable piece of furniture. Then, you express your will upon the world directly by crafting the supplies, your knowledge, and the tools together to produce a bookshelf. You’ve exercised your spatial reasoning, planning, tool discipline and technique, and so on.

Engineering should be just like that: you know what the software needs to do, what sorts of platforms and languages are appropriate to express the requirements, and with experience, the design patterns and architectures that are likely to result in a stable piece of software. Then, you express your will upon the computer directly by crafting syntax, your knowledge, and infrastructure together to produce the application. You’ve exercised your problem solving, planning, architecture and design acumen, and so on.

Now imagine you’re trying to tell an LLM to build a bookshelf. What skills are you exercising? You’ll learn the particular quirks of that model and how to phrase prompts with enough detail that it understands what sort of bookshelf you’re looking for. Then, if you’re lucky, you end up with a bunch of mismatched prefab pieces that you have to assemble like you went dumpster diving at Ikea.

I have two FJÄLLBO shelves from Ikea myself, you know.

As I’ve already alluded to, if you’re a hobbyist and you just need a dang bookshelf, there’s nothing wrong with an Ikea bookshelf. But if you’re a professional furniture manufacturer and all you do is bash pieces of prefab furniture together and call it a product worthy of sale to a client? It doesn’t cut it. You’re scamming your customers, and you never learned how to actually build bookshelves. You don’t know how to plan for materials because the pieces were prefabricated, you can’t figure out how to fix problems because you don’t understand how they’re made, and you don’t have any tool discipline or technique so you’re highly likely to chop off your fingers trying to cut the wood.

(Before you take this all too literally and tell me that furniture companies source their prefab pieces from multiple manufacturers and resell them as a cohesive unit, yes. I understand that. However, someone had to understand how a bookshelf is made well enough to know that the pieces would fit together, look good together, where to source them from, how to forecast supply from their vendors to meet the demand for their downstream product, and so on. If you want to keep abusing the metaphor, though, and you think you’re the reseller instead of the manufacturer of the pieces, then try this. Pretend that you’re building a SaaS website. You don’t write your own database, web server, application framework, infrastructure framework, or any of that. But you still have to understand how to build your service’s bespoke value-generating logic and how to utilize those “prefab” components to do it.)

Who Are They?

If vibe coding is so detrimental and generates such poor problem solvers, you might be asking who are these so-called vibe coders then? Do they even exist, or are they just a figment of the imagination in the minds of AI tycoons? No, it’s indisputable that they exist. If you’re working in the industry today, chances are very good you know one or more of them.

Sometimes, they’re burnt out or distracted, but obviously need to keep their job. So they turn to LLMs as a way to keep producing code without having to engage. Other times, they agree with the (toxic) mindset that the only priority is churning out code without much regard to any of the principles or disciplines of engineering. You know, the stuff we worked for decades to figure out was absolutely necessary for the longevity of software.

The vibe coders that worry me the most, though, are the new developers entering the industry now. As an unregulated, uncertified discipline, software engineering is incredibly vulnerable to cargo cult practices and cynically-motivated fads. These newbies are getting fed all kinds of counterproductive codswallop by an industry that absolutely does not have their best interests in mind. One of the more public meta-voices of the tech industry, The Primeagen, reported on how the overreliance on LLMs is stripping junior developers of the critical foundational “muscle memory” they need to succeed.

Ten years ago, we used to accuse bad developers of just copy/pasting code from Stack Overflow. Vibe coders are a similar phenomenon, except now they’re not even getting exposed to the community interactions around those posts. But so long as IT remains a lucrative career, there will always be people looking to get in without doing the prerequisite work. Just like with Stack Overflow, LLMs are a crutch, and some people never get back on their own two feet.

Good Vibrations

Vibe coding doesn’t teach you to be a good programmer, engineer, teammate, or problem solver. It only teaches you how to be a good LLM-wrangler, and no one arguing in favor of vibe coding today is arguing that it generates quality code. They’re not even arguing that it’s easy; most vibe coders acknowledge that they have to spend a decent chunk of time fixing issues it creates. They’re only arguing that it’s good enough, and I think that’s demonstrably false. That doesn’t mean you should necessarily avoid LLMs wholesale. My point is that they should be just that: tools in your broad arsenal of problem solving strategies. At least for now, an LLM can’t be a problem solver, and you can’t be a problem solver if you rely too heavily on them.

I still have hope. There’s still time for us to influence new devs to engage with the principles of engineering. We can still hold ourselves accountable to being the best versions of ourselves. I also know that this “race to the bottom” era will end as soon as the consequences start piling up. Investing in yourself is never a bad investment; you’ll want to be primed for the rebound instead of lagging behind.

Perhaps most importantly, don’t betray yourself. Problem solving is as much a creative expression as it is a scientific one, and LLMs are still purely derivative. This is your advantage in the AI-obsessed industry we find ourselves part of today.