Doom Eternal is a strange game. Despite being a huge fan of the Doom series since I was a kid, and even though I greatly enjoyed Doom (2016), I bounced off of Eternal for a while. I loved the Heavy Metal aesthetic (and soundtrack), found the weapons incredibly satisfying, and connected well with the new movement mechanics, yet something didn’t click with me at first. The hype died down pretty quick and I was left frustrated, racking up a lot of deaths.

The game is hard. I started playing on the “normal mode”, Hurt Me Plenty. By the fourth level, I cranked it down to easy mode (I’m Too Young to Die) and still kept getting wrecked. Sure, I was making more progress, but I could tell something wasn’t right. My initial reaction was that the game was just too damn difficult. I’ve played difficult games before, but Doom Eternal felt different. I put the game down for a while.

Speedruns to the Rescue

My inability to enjoy the game didn’t stop me from watching its speedruns. Specifically, I started tuning into Byte’s stream and watched his Ultra Nightmare 100% attempts. He’s not the best Eternal player out there, but I found his style entertaining and had enjoyed his Doom (2016) run at AGDQ 2020. At first, I was just wowed by his mastery over the mechanics. While watching, though, I started to pick up on some patterns.

He used the flame belch (lovely name, right?) far more than I did, and on the weakest enemies. He never ran out of ammo, somehow, while I was always low. He seemed to throw freeze grenades at heavy demons and then move away from them instead of closing the gap to kill them. Noticing all this inspired me to get back into the game and start experimenting more with the tools at my disposal.

Instantly, I was 1000% better at the game and beat it, no problem, on Ultra Nightmare… is what I hoped would happen. Instead, I still got my ass kicked repeatedly on easy mode. But I was learning. I figured out that the flame belch doesn’t spawn armor shards just because. It spawns them as a renewable way to refill your armor, and armor is better than health. The chainsaw regenerates a charge of fuel because you’ll quickly run out of ammo if you don’t replenish it; the ammo limits are significantly lower than the previous game for a reason. The freeze grenade is a crowd control tool, offering you an opportunity to get some distance and reevaluate your situation.

Perhaps most importantly, I started having fun again. Where before the game felt difficult to the point of frustration, now it felt like it was challenging me to do better and learn more about its mechanics. I kept improving until eventually I felt comfortable moving back up to normal mode, where I promptly got stomped again. But I didn’t feel too bad about it this time. I understood the game on a much deeper level than I did initially, and knew that success was within reach. I just had to get good, basically.

Difficulty and Challenge Are Not the Same

I’ll be honest: the “correct” way for my Doom Eternal story to end would be for me to say that by understanding it, I was able to beat it. It would feel like the natural conclusion. But no, I actually never beat it. Don’t get me wrong: I got much further, and I didn’t stop playing because of that original frustration this time. I probably will eventually circle back around and finish the game—like a lot of folks, I’m spoiled for choice when it comes to entertainment, and other things grabbed my attention.

Despite having not finished it, my experience with Eternal left an impression on me about the contrast between difficulty and challenge. People tend to use the words interchangeably, but I think there’s a very clear distinction between them. Indeed, a challenging game is difficult, but a difficult game isn’t necessarily challenging.

Difficulty in a game (or in most activities, for that matter) is when something requires a great deal of investment to achieve. The difficult action is non-trivial to complete successfully. Critically, however, there is no implication that the investment be tied to skill, talent, or practice. Something can be difficult to do simply because it’s very time-consuming.

- Hitting the max level in Final Fantasy VII is difficult, but it’s not challenging. If you spend enough time grinding, you’ll get there, and the grinding is mindless busywork (i.e. it requires little thought or input).

- Finishing Dragon Quest II is difficult. Many of the enemies in the end game can kill your party in a single action. Luck is more of a factor here than anything else.

- Many roguelike games (e.g. Nethack) are incredibly difficult to complete. The difficulty lies in deep randomness, but challenge can be found in strategies to mitigate it.

- Battletoads is a difficult and challenging game, but many facets of its difficulty originate from unrealistic and unfair mechanics which can only be addressed by rote memorization.

- This is true of many older arcade- and NES-era action games. These games were designed to keep you playing even when the quantity of game content was low. This is especially true for arcade games, where the goal is to keep you pumping quarters into the machine.

- Hundreds of mobile games (and, increasingly, big budget retail releases) are very difficult, but can be made easier through purchases or time-gated resources. This difficulty cannot be overcome through skill; it requires an investment of time and/or money.

I don’t mean to imply a lack of challenge in these games. Going back to the Final Fantasy VII example, a skilled player with a good strategy will complete the game more quickly than one without. But ultimately, the game can be completed, more-or-less, by anyone.

Challenge, on the other hand, is when the action cannot be accomplished successfully until you perform it better. “Better” usually means past a designated threshold of skill, but can sometimes be on a sliding scale of judgement based on the goals of the game (think the scoring system in Devil May Cry). Some difficult games can be brute-forced, while by definition a challenging game cannot—unless the repetition results in skill improvement, of course, but then we just call it practice.

- Doom Eternal turned out to be a very challenging game for me. Until you understand the rules of the game and gain some skill at the necessary tactics and mechanics, you will reach a point where you can no longer progress.

- Dark Souls is famous for being a highly challenging game.

- The mainline Mario games often offer a natural scale of selectable and/or optional challenge, but even at the lowest levels, almost the entire game design is built around challenge.

- The required challenge may not be very high, but it’s there nonetheless, especially for newer players who possess less baseline skill. Not everyone is intimately familiar with the hand-eye coordination and mental mapping necessary to move a character in 3D space with a controller.

To put it succinctly, challenging games are literally encouraging you to get better at them through their design.

Challenge Is Not Necessarily Fun

So far, this article has painted a fairly negative picture of games that possess a high level of difficulty without necessarily having challenge. I even said that once I discovered the challenge of Doom Eternal, I started having more fun. The truth, though, is that the fun factor of a game is not exclusively tied to its challenge or difficulty.

Let’s look at the Final Fantasy VII example again. It’s a highly regarded classic, often topping peoples’ “best games of all time” lists, but as I said earlier: the game can be beaten by pretty much anyone. This means it has no challenge, right? Well, maybe not in the core game, but players seeking a challenge actually have several options.

- They can take on the optional superbosses, whose defeat requires more than just grinding XP and reaching max level.

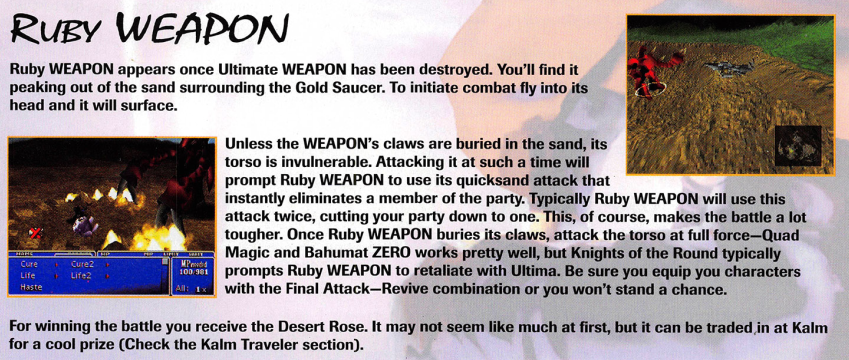

- Ruby Weapon and Emerald Weapon are much more challenging fights than anything in the core game.

- Today, the age of the game plus the drastically increased availability of internet access has made strategies for killing them commonplace.

- Back in the day, though, everything was hearsay. They were shrouded in rumors and even the strategy guides didn’t have great tips for how to beat them. Finding someone that had was genuinely impressive.

- They can just force themselves to play more intelligently and optimize their gameplay more.

- For example, rather than just leveling up every time you lose to a boss, these players might retry several times with different tactics.

- They can enforce their own gameplay restrictions.

- This is a niche audience, to be sure, but it’s one that enjoys taking otherwise “easy” games and making them challenging through intrinsic objectives such as not equipping Materia or shooting for the lowest possible character level at the end of the game. Speedrunning falls into this category as well.

But what if you just don’t want to be challenged? Isn’t it valid to want to enjoy an experience like Final Fantasy, with its intricate story and elaborate cutscenes and grand adventure, without having to get good? What about players with disabilities, or those with little capacity to practice a video game for long periods of time? Many games are tailored around the experience of playing them without necessarily requiring a show of skill to “earn” that experience, and that’s okay too.

Not every game needs to be challenging. Presenting an obstacle to overcome is only one of the many tools in the design toolbox that can make something fun. Sometimes, challenge is a barrier to enjoyment. Take Dark Souls, for example. I’ve never beaten it. Hell, I’ve barely made it past the starting area. Despite that, I still enjoy the game’s atmosphere, lore, and art. For me, it’s the perfect Let’s Play game. I’m not interested in putting in the effort of gaining the skill necessary to see more, and the pleasure I get from overcoming the challenges doesn’t outweigh the frustration I feel with myself when I continually fail. Since I enjoy the presentation of the game, though, and find its gameplay loop interesting (in theory), I also enjoy watching others play it and discuss it.

Every Game Has Its Place

The intangible elements that make a game fun are extremely hard to pin down. Plenty of awesome games are challenging, tons of amazing games are easy, and games exist on every point in the diamond-shaped spread between ease, difficulty, accessibility, and esotericism. There is a place for all games, whether they challenge you to be better or not. It’s very interesting to me how often I see difficulty conflated with challenge, however. I think the industry would do well to learn the difference and better identify where designers are substituting challenge for plain difficulty.