Baby’s First Game

I wrote my first game when I was 12.

I had grown up on video games—my parents tell me I was playing Mario before I was 3 years old—and I always wanted to make my own. But, to make video games, I had to learn how they were made. My 12-year-old self managed to figure out that I needed to learn programming, and games were usually written in C++. So, naively, I assumed that if I could just learn C++, I could make games. My parents and I were at a bookstore one weekend and I spotted a book: Sam’s Teach Yourself C++ in 21 Days. “Wow,” I thought. “Just 21 days? I’ll be making games in no time!” I begged and pleaded for them to buy it for me, and after some discussion, they did.

I was lucky enough to grow up in a very technology-rich household, much to the chagrin of my parents’ credit ratings. They loved having hi-fi stereos, game consoles, and of course, multimedia PCs… whether they could afford them or not. But as a result, I had grown up surrounded by games: NES, SNES, Genesis, Playstation, and PC games. My dad was also particularly proficient (for the time) with this stuff, and he taught me how to play MUDs via Telnet. Eventually, he introduced me to EverQuest; it lit up my young brain like a Christmas tree.

So, 12-year-old me sat down in front of the computer with an outdated (even at the time) C++ book and started reading. I don’t know what the curriculum is today, but at my school in 2000, I had only just started learning algebra (and even then, only because I opted into an accelerated learning path). So when I first got started, I didn’t really even understand the concept of variables. Instead I did what most starting programmers used to do: I typed out all the examples and started tweaking them.

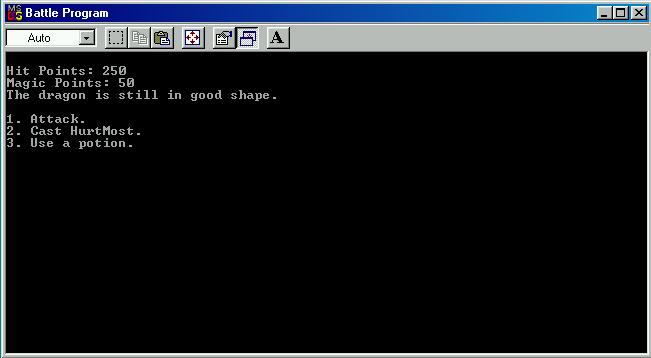

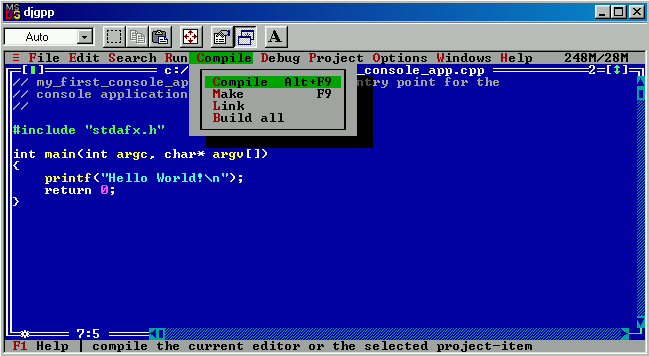

Very much not state of the art, even in 2000

I noticed that all the examples in the book focused on text-based output. That wasn’t exactly what I wanted; where were the flashy graphics and explosions? But, since I had some experience with MUDs, I knew I could make a text-based RPG. I did all my editing in a DOS-based environment called DJGPP, because that’s what the book shipped with on the included CD. My code was probably one long int main() function full of the kind of cyclomatic complexity that would make your head explode.

Yet, there it was. After reading (parts of) the book and really committing to the task, I had debatably learned to program. It took longer than 21 days, that’s for sure, but I made my first game. It had an enemy that could attack you, you could attack it back, and the stats all worked. If you defeated the enemy, you got a little “congratulations” and then the program ended. That’s it. Baby’s first game.

Obsession

The itch to write more games hit me hard. I sent my game to all my friends, who undoubtedly never bothered unzipping it but told me it was cool anyway. Then, I started thinking about what comes next. I had grand plans in my mind of starting a game studio in my garage with my friends and acquaintances. Some of them played music, some of them drew, and some had expressed interest in level editors for games like Half-Life. It felt like we had all the ingredients.

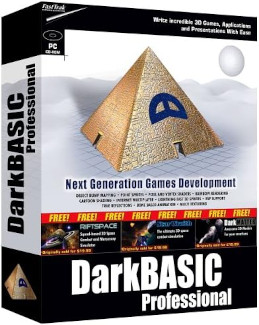

My friends and I had LAN sleepovers where we’d play games, of course, but also have little game dev jams. I discovered DarkBASIC, a BASIC interpreter stapled onto a DirectX helper API, and it blew my mind. Not only was BASIC so much easier than C++, DarkBASIC had all these graphics and sound commands built in, and it even loaded Half-Life maps straight out of Hammer! All the pieces were there.

DarkBASIC Pro

My friends and I put together several stupid little games over the next few years. We tried building an FPS, we did some experimenting with a Final Fantasy-style RPG, we had a trivia puzzle game, and we even started a Castlevania-style action platformer. This was an era before Unity, Unreal, or Godot had commoditized game toolkits. As the only programmer for most of these projects, I had to learn a lot. Game engines, realtime simulations, asset pipelines, data structures—as the games got more complex, my skills had to grow to accommodate.

I dabbled in OpenGL, DirectX, various open source game engines, and learned a little bit of 3D math to try and make it all make sense. I wrote code in BASIC, C, C++, C#, Lua, and probably more. We found copies of 3DS Max and Photoshop, discovered Blender, and tooled around with RPG Maker 2000. There was so much to explore, so much to learn, and so much time to spend on it. After all, we were relatively privileged teenagers. What else did we have to do? Schoolwork? Psh.

The Real World

All told, we probably started and worked on 15 different games over 6 years. We only really “finished” a few, and they were all messy hobby efforts full of copyrighted assets and bad ideas, but that’s how you forge a real skillset. You learn by doing new things… and we did a lot of new things.

By the time we graduated high school, I had become a legitimate programmer. Even for a couple years following, we kept going, getting more and more professional and developing our talents. I think if we’d managed to get better a little faster, take it a little more seriously, and make a few different decisions, we could’ve really achieved that dumb little childhood dream of starting a game studio in the garage.

Unfortunately, the real world is harsh to naivety. We all went off to college after high school, and our interests wavered as they had to compete with things like… you know, relationships, jobs, other hobbies, stuff like that. Suddenly we had responsibilities. I also hit a severe bout of depression for a few years which made it hard to do much of anything at all.

Me, basically

By the time I was 21, not even a decade after I started making games, I had stalled out. When I was 22, I decided it was time to “get a real job.” Until then, I had been going to college and working various part time jobs, splitting an apartment with my then-girlfriend (now wife). I considered getting a job in the game industry, but by 2010 it was widely known just how miserable the working conditions were. I made the painful decision to let game development remain a hobby and start a traditional IT career instead.

A Real Job

Never let it be said that I don’t commit. When I decided to get a “real job,” I went at it pretty hard. Thanks to my prior game programming experience (and some SQL fundamentals in college), I entered the industry as a Software Engineer II. From there I made my way up the ladder for 15 years, learning and growing along the way, until suddenly I found myself as a Senior Director of Engineering.

Being a professional engineer, leader, and mentor taught me more than I could possibly write here. I could fill a pretty fat book with the lessons I learned, decisions and mistakes I made, values I came to hold dear, and so on. The most important thing I took from it, though… is that I’m worthy of being a leader. Even as far back as my “garage game studio” days, I doubted whether I was the right person to lead such a thing. I never saw myself as a leader.

Even once I made my way into a career leadership position, I still didn’t see myself as a leader. I was just the guy who did what needed to be done, whether that was setting direction for a team to align with business goals or working out the architecture for a new project. It took a long time of gradual self-reflection for me to realize being a leader isn’t about any of that shit you read on LinkedIn. It’s about being trustworthy and responsible, about being decisive and knowledgeable, and about putting your team over yourself.

I’ve met too many so-called leaders who fail at this. Miserably.

Reflections

At time of writing, I recently lost my “real job.” Don’t worry, I’ll be fine - but for the first time in 15 years, all the noise and anxiety of my day job has gone quiet. I’ve finally had a chance to stop and think about that decision I made so long ago.

At various points since that decision, I’ve worked on games in my spare time. I still write down all my ideas. I’ve made multiple concerted efforts to spend nights and weekends on game projects, and while I don’t have much worth uploading here to my site, I constantly feel that itch in the back of my mind: make video games. It’s the one aspiration on which I’ve never really wavered.

Of course, tech evolves fast. To keep up with my career, I’ve had to devote many long nights and weekends to working late, being on call, or just keeping up with the latest advancements. I devoted so much of myself to my day job that, by the end of the day, my brain was empty and I didn’t want to sit in front of an IDE for another 4-6 hours. Hell, sometimes I just wanted to sit down and watch a movie with my wife.

Some particularly grind-minded individuals would probably call those excuses. Others would accuse me of not really enjoying game development, if I don’t feel like doing it after a 10 hour work day. I’m sure there’s some small amount of truth to those statements - that I could be more passionate - but like most gatekeepers, they hold everyone to an unreasonable standard to make themselves feel better. It’s reasonable to be human.

But what if now is the time?

The Exceptions Which Prove The Rule

I've got about 50 hours in this game...

If you haven’t already, you should read LocalThunk’s timeline of his development on Balatro. It tells story of a man who made games as a hobby for a long time, ended up quitting his job to work on his passion project, and found massive success.

Or how about the story of poncle (Luca Galante), developer of Vampire Survivors? A man who made games both as a hobby and professionally, ended up quitting his job to work on his passion project, and found massive success.

Go back far enough and you might even recall the story of Notch, and a little game called Minecraft. He turned out to be a real piece of garbage, but few can deny the wild success of his passion project. How did he make it happen? Well, he quit his job to work on it.

If you were starry-eyed enough, like me, you might read stories like these and think, “Wow, all I need to make it as an indie dev is a passion project, hard work, and some luck! I can do this!” You might even be correct, technically… but it’s not what you think. Here’s my estimated breakdown:

- 0.1% passion

- 0.2% hard work

- 99.7% luck

For every LocalThunk, poncle, and Notch, there are 1,000 aspiring indie developers whose games rot in the back catalog of Steam. Some of those games are trash, certainly, but some of them are fantastic gems. They just haven’t sold. No streamers have played their game yet. No publishers were interested in picking them up. Most of those games will fade into the ether, and their developers will end up back at their day jobs (or worse).

Balatro, Vampire Survivors, and Minecraft are exceptions which prove the rule: the indie game market is unimaginably overcrowded. Your chance of success in this market is almost zero. Are you financially dependent on your game being successful? Don’t become an indie dev. It’s more akin to playing the lottery than working a day job.

That’s the general guidance, anyway. Hell, even several successful indie developers have said the same thing. After reading this article about Slam Bolt Scrappers on Penny Arcade back in 2011, I reached out to the studio head, Eitan, for advice. He responded (props to him) and more-or-less told me exactly what I already knew, deep down.

I wouldn’t recommend quitting your day job unless you really have a game plan for it.

I only learned while doing research for this article that his studio, Fire Hose Games, ran out of money and went out of business last year. Their final game, Techtonica, has a Mixed rating on Steam. Their socials are silent… it appears they petered out unceremoniously.

I can’t say anything. I didn’t buy the game either.

Existential Conflict

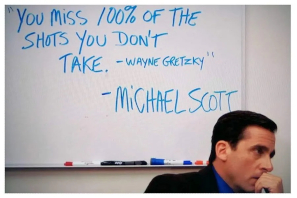

The raging existential conflict which has agonized me for 15 years is this: you miss all the shots you don’t take, but it’s super risky to take the shot. I can never be successful if I don’t try, but it’s extraordinarily likely I won’t be successful even if I do. It’s gambling.

I don't even watch The Office, but...

Am I willing to gamble away my livelihood for the chance to fulfill my childhood dream?

One of the recurring elements among all the stories I told earlier - LocalThunk, poncle, and even Notch - is that they worked on their games in their spare time. Nights and weekends, while working a day job, until some threshold was crossed where they began to see a legitimate chance of success. Eitan from Fire Hose warned me 14 years ago not to quit my day job.

Earlier I said that it’s reasonable to be human. Maybe, though, if I really want this so bad… it’s not. Perhaps, until I can find the energy and focus within myself to power through my day job for 8-10 hours and then stare at the IDE for another 4-6, I don’t have what it takes. Am I really “obsessed” with game development if I only want to work on it while my brain is fresh? Do I even deserve it?

I don’t know. I’ve never known, and it’s part of why I originally made the decision. It gnaws at me constantly.

So Now What?

A small peek behind the curtain: this article took me a long time to write. I decided to take a few weeks off work between jobs—my wife and I just moved 4,000 miles across the entire continent of North America and I wasn’t, originally, going to get a break to rest. Starting this article is one of the first things I did after we moved into our new place. Other posts have taken longer, but none have been so personal.

This has been my way of reminding myself why I decided, in 2010, to get into traditional IT instead of trying to be an indie game developer. It’s been me painfully navigating the same decision yet again. As a kid, all I ever wanted was to start a game studio with my friends and make games for a living. How naive and selfish.

The recipe for success is to tighten up the graphics on level 3

Still, despite all the advice to the contrary, all the obvious signs that the industry is flooded, and all the common sense and risk assessment telling me it’s stupid, there’s a huge part of my inner self tied up in the desire to make games. To get something creative out there that people enjoy and leaves an impact on their lives in some way… that’s what drives me.

The tech industry right now is so far abstracted from making products people want to use. It’s all caught up in hype cycles and massive bubbles; meanwhile, the products we actually depend on day-to-day are rotting away or being hollowed out to make room for AI. I hate it. I just want to make cool things that make people happy.

I don’t yet know where I’m going to end up. Professionally and personally, it’s a time of major change for me at what might end up being one of the worst possible times in history to make major changes. All I know is that wherever I land, it’s going to be somewhere that I can meaningfully contribute to, and perhaps even lead, a product that actually impacts someone.

That’s all I want: to make a positive impact on the world, however small. Is that outmoded now? I guess I’ll find out. Check back here in a few months to see if I’m starting a GoFundMe to help pay my bills…